Today I spoke on a panel at the United Nations Forum on Business and Human Rights in Geneva.

Our event was on Challenges and Opportunities of a Treaty Addressing Corporate Abuses of Human Rights.

The Treaty is being drafted by a Working Group of the UN Human Rights Council. Baby Milk Action is part of the Treaty Alliance of civil society organisations that have signed joined statements in support of a binding Treaty.

Here is the text of my intervention today:

Thank you for the invitation to speak and to you all for coming.

Baby Milk Action is the UK member of the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), consisting of more than 270 groups in over 160 countries.

We monitor the baby food companies against UN marketing standards adopted by the World Health Assembly.

Specifically the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, which was really the first attempt to set standards for an industry sector at the international level, long before the Tobacco Convention.

The first point I would like to make is the Code was developed through a process of consultation with interested parties, not negotiation. The mandate of the World Health Assembly is health and, quite rightly, it put health before business interests.

If we are serious about protecting human rights, we have to put human rights before business interests. Business should be consulted, of course, but human rights should not be negotiated away.

We need the measures that are necessary, not just those that will be tolerated by business.

Implementing the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes in national measures is recognised as a requirement to fulfil Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, giving the Code status in international law. Our partners at IBFAN-GIFA here in Geneva have provided support to national campaigns in using the Convention.

Today over 70 countries have introduced legislation implementing the Code and subsequent, relevant Resolutions adopted by the World Health Assembly.

Though this is in the face of industry opposition and enforcement varies in effectiveness.

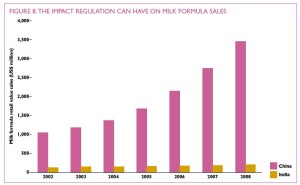

Implementation of the Code and Resolutions helped Brazil to reverse the decline in breastfeeding that had occured there. In India formula sales remain static, whereas they are growing exponentially in China [graph left from Euromonitor, included in Save the Children report Superfood for Babies].

Implementation of the Code and Resolutions helped Brazil to reverse the decline in breastfeeding that had occured there. In India formula sales remain static, whereas they are growing exponentially in China [graph left from Euromonitor, included in Save the Children report Superfood for Babies].

The World Health Organisation’s latest statistic is 800,000 children die every year through not being optimally breastfed, so there is still much to be done.

But our experience shows the importance of having an international legal framework for regulating corporations.

A big concern remains, however: what happens when regulations do not exist or are not enforced?

IBFAN monitoring shows systematic violations are commonplace where baby food companies think they can get away with them.

So we would like to see some sort of complaint, investigation and enforcement mechanism at international level included in the Treaty.

Not just home nation responsibility for the actions of their corporations in other countries, but an international system for when national measures fail.

Home nations may be reluctant to put their corporations at a competitive disadvantage by taking more robust action than other countries, so there needs to be an international mechanism as well to create a level playing field.

We know that some governments argue that regulation at international level is unnecessary because, so they say, corporations can be persuaded to change their behaviour through the UN Guiding Principles and initiatives such as the UN Global Compact. The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises are also held up as a reason not to introduce binding regulations.

We have brought complaints using these non-binding mechanisms. (Full details here).

Although the UN Global Compact stresses it is not compliance based initiative, it does claim to be accountable. It also says this, to quote:

“Nevertheless, safeguarding the reputation, integrity and good efforts of the Global Compact and its participants requires transparent means to handle credible allegations of systematic or egregious abuse of the Global Compact’s overall aims and principles.”

The UN Global Compact publishes company Communications on Progress on its website, including Nestlé’s Creating Shared Value reports. It has even launched a Nestlé report at a joint event. This gives Nestlé a very good image, but this is undeserved.

The information in the reports is misleading.

We registered complaints with the UN Global Compact Office under so-called Integrity Measures as part of a coalition of Nestlé Critics. Not just about baby food marketing, but trade union busting; failure to act on child labour and slavery in its cocoa supply chain; exploitation of farmers, particularly in the dairy and coffee sectors; and environmental degradation, particularly of water resources. (Click here for report).

We got nowhere with the UN Global Compact Office. It stressed that it is a voluntary initiative, aimed at facilitating communication and dialogue.

Yet under the Integrity Measures it could provide advice and guidance to remedy the situation. It can review company responses and exclude a company from the initiative if it is responsible for egregious violations and bringing the initiative into disrepute.

The Global Compact Office refused to apply these measures to Nestlé, a patron sponsor of its events.

In fact, the Global Compact Office has told us that no company has been excluded following a civil society complaint.

So Nestlé continues to use its lauded position in the Global Compact to divert criticism.

[Read our correspondence with former Global Compact Executive Director, Georg Kell, over the failure to apply the Integrity Measures].

We got no further with the Swiss National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines. It also said its role is to promote dialogue.

We are in communication with senior executives of Nestlé. We don’t need help in communicating. What we need is action when executives refuse to abide by human rights norms.

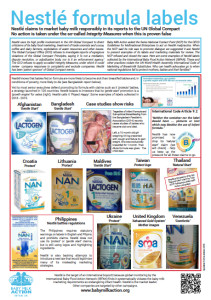

The Swiss National Contact Point wanted a specific example, so we highlighted how Nestlé claims its formula “protects” babies. It does this even though it knows babies fed on formula are more likely to become sick than breastfed babies and, in conditions of poverty, more likely to die.

We suggested the National Contact Point ask Nestlé for copies of its labels and materials for review as part of its dialogue strategy. It refused to do so and closed the case.

We have gathered examples through IBFAN monitoring and you can see some on this sheet. We have to campaign to stop these violations because these other systems fail to do so.

We have gathered examples through IBFAN monitoring and you can see some on this sheet. We have to campaign to stop these violations because these other systems fail to do so.

When people say the UN Global Compact and OECD Guidelines make a binding Treaty unnecessary, we disagree.

We need a Treaty with strong mechanisms.

We put forward some possibilities for mechanisms for remedy as part of a Task Force of the UN System Standing Committee on Nutrition which looked at Global Obligations to the Right to Food. This led to this book with that name.

One idea is to make it a legal requirement for Corporate Social Responsibility reports to be truthful, with a board member legally responsible for them, as happens with company accounts.

There could be an international public prosecutor to take legal action at some form of international court if a preliminary investigation of complaints finds there is a case to answer.

To change behaviour any sanctions have to be meaningful. We see fines applied at national level are generally so small to corporations that they seem them as a minor business cost. If fines were linked to turnover as in some other areas, this is more likely to prompt executives to stop violations.

To change behaviour any sanctions have to be meaningful. We see fines applied at national level are generally so small to corporations that they seem them as a minor business cost. If fines were linked to turnover as in some other areas, this is more likely to prompt executives to stop violations.

These are just ideas for discussion.

[Also see the article by Mike Brady and Patti Rundall in the SCN Journal: Governments should govern, and corporations should follow the rules].

I hope the Treaty process will look to imaginative ideas to protect human rights and will bring in measures that are necessary, not just those that will be tolerated by business.